The "Good for Her" genre explained

And why we're about to see a whole lot more of it across literature, film and television.

Note: the terms “women” and “woman” used throughout this essay includes all trans and female-identifying people.

I think we all need to collectively take a huge deep breath and then release it in a scream that would summon the gods. Because what the fuck is even the world right now.

We are living in the most insane dystopian timeline where people are saying the quiet part out loud about how racist, homophobic, misogynistic and ableist they really are. Elon Musk literally just did the N*zi salute at Trump’s inauguration. We are living in hell.

Every day I wake up with new reasons to be furious and I’m not quite sure what to do with all this anger.

Perhaps this is why I’ve found myself turning to dark, “unhinged” fiction more and more as a reprieve from reality. It sounds counter-intuitive, why read something awful when you’re already feeling awful? But I find a strange comfort in reading about worlds where the oppressed fight back, usually through non-traditional methods.

There’s a newly coined term for this genre of literature, and film and television:

Good for her.

The "good for her" literary genre (or trope) is a term often used to describe books, stories, or media where women reclaim their agency, often through morally ambiguous or unconventional actions.

These stories usually center on women making bold, sometimes shocking choices to escape oppressive situations, assert independence, or seek justice—even if it means burning bridges, breaking norms, or acting unethically.

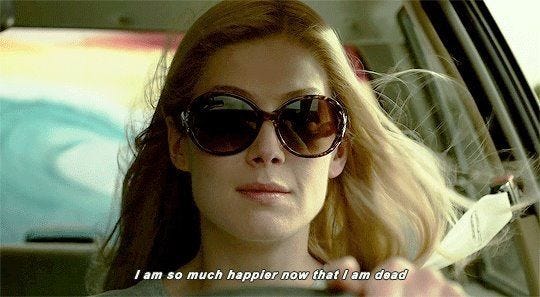

The phrase "good for her" is often ironic, used by audiences to express darkly humorous approval of the character’s actions, even when those actions are destructive or extreme.

Origins and Evolution

The “Good for Her” genre began as an internet meme, a darkly humorous reaction to stories of women breaking free from societal or personal oppression—often in extreme or morally complex ways. Over time, the term gained traction as a way to describe a broader category of literature and media that resonates with feminist ideals and cultural discontent.

Core Characteristics:

Protagonists: These stories centre around flawed, multidimensional women who defy traditional archetypes.

Themes: Liberation, revenge, and autonomy are key themes.

Tone: Often ironic, darkly humorous, or cathartic in its exploration of rebellion and justice.

Distinction from Other Genres

While it shares elements with revenge narratives and feminist literature, the “Good for Her” genre differentiates itself through its embrace of moral ambiguity. Unlike traditional empowerment stories, these tales don’t demand their protagonists be virtuous or their choices palatable.

Characteristics of the "Good for Her" Genre:

Revenge and Justice

At its core, the “Good for Her” genre is often about righting wrongs. Protagonists take justice into their own hands when societal or legal systems fail them, as seen in Promising Young Woman where Cassie meticulously confronts systemic misogyny. These acts of vengeance are both personal and symbolic, challenging larger societal injustices.

Liberation from Oppression

Many stories in this genre depict women breaking free from toxic relationships, suffocating societal roles, or oppressive circumstances. In Thelma & Louise, the titular characters escape patriarchal violence and expectations, choosing freedom at any cost. Similarly, in The Bell Jar, Esther Greenwood’s mental unraveling becomes a form of resistance against the societal expectations placed on women in the 1950s.

Complex Morality

A defining feature of this genre is its embrace of moral complexity. The protagonists’ actions often blur the lines between right and wrong. Amy Dunne in Gone Girl is both a victim and a manipulative anti-heroine, inviting audiences to grapple with conflicting emotions of admiration and repulsion.

Subversion of Gender Roles

By rejecting expectations of passivity or victimhood, “Good for Her” stories position women as agents of their own fates. Dani’s transformation in Midsommar from a grieving girlfriend to a triumphant May Queen subverts the trope of the damsel in distress, redefining empowerment in the process.

Examples of the "Good for Her" Genre

Literary Examples

Gone Girl by Gillian Flynn: Amy Dunne’s calculated schemes challenge the notion of the “perfect wife” and redefine the anti-heroine archetype.

My Year of Rest and Relaxation by Ottessa Moshfegh: The protagonist’s unconventional journey to self-healing involves isolation and narcotic-induced sleep, defying societal norms of productivity and wellness.

Film/TV Examples

Midsommar: Dani’s ultimate liberation through the destruction of her old life is both horrifying and cathartic.

Promising Young Woman: Cassie’s calculated vengeance and tragic ending leave viewers questioning their own definitions of justice.

Short Stories and Other Media

Carmen Maria Machado’s Her Body and Other Parties: Through surreal, feminist storytelling, Machado explores themes of female agency and rebellion against societal constraints.

The appeal of the "good for her" genre lies in its cathartic exploration of rebellion, autonomy, and the reclamation of power, even in unconventional or extreme ways. It challenges societal expectations of how women "should" behave, creating space for complex and unapologetically human characters.

Why the genre is growing in popularity

In December 2024, the New York Times ran a guest essay titled The Disappearance of Literary Men Should Worry Everyone by David J. Morris.

In it, Morris expresses concern at the dominance of women in literature as both readers and writers, and the increasing absence of men.

It’s a strange piece. Morris discusses the “issue” of male underrepresentation in literature, but quickly follows paragraphs like the below with statements claiming he welcomes the rise of women… but also doesn’t? Because otherwise why would he write this piece:

Male underrepresentation is an uncomfortable topic in a literary world otherwise highly attuned to such imbalances. In 2022 the novelist Joyce Carol Oates wrote on Twitter that “a friend who is a literary agent told me that he cannot even get editors to read first novels by young white male writers, no matter how good.” The public response to Ms. Oates’s comment was swift and cutting — not entirely without reason, as the book world does remain overwhelmingly white. But the lack of concern about the fate of male writers was striking.

To be clear, I welcome the end of male dominance in literature. Men ruled the roost for far too long, too often at the expense of great women writers who ought to have been read instead. I also don’t think that men deserve to be better represented in literary fiction; they don’t suffer from the same kind of prejudice that women have long endured. Furthermore, young men should be reading Sally Rooney and Elena Ferrante. Male readers don’t need to be paired with male writers.

I have to say, the “issue” of male underrepresentation in literature is something I really could not be less concerned about. I read a comment on Instagram that perfectly captured how I feel about this supposed problem:

It is no coincidence that the rise of women in literature corresponds with the boom in “Good for Her” narratives.

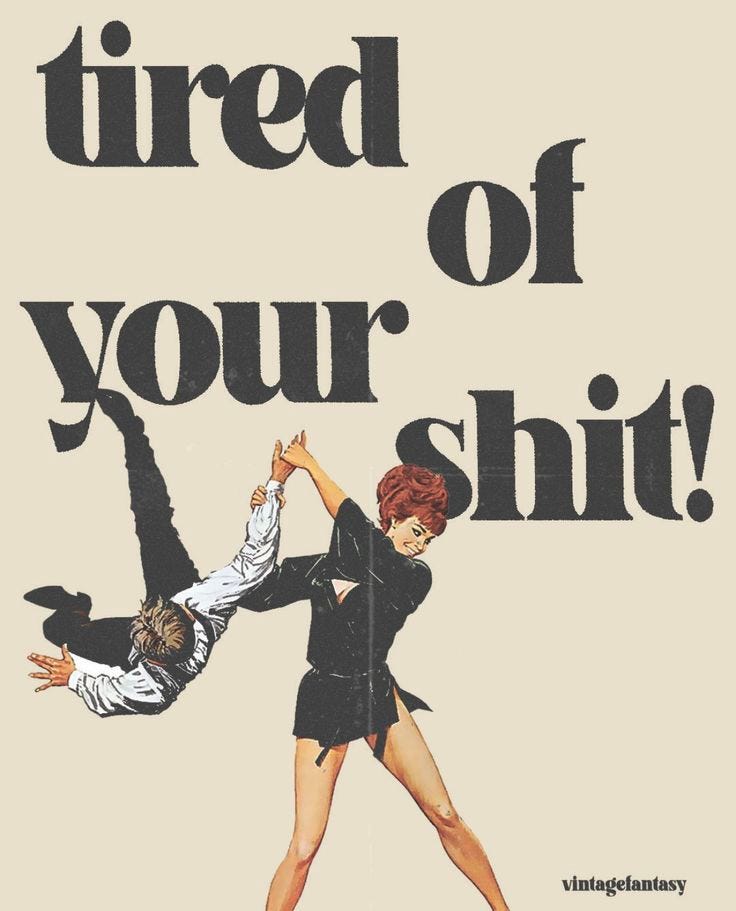

Women are extremely adept at suppressing rage. Speaking for myself (even before the world’s richest tech dweebs formed an oligarchy that will lead to our doom), I usually walk around with a constant simmering fury, mostly low-level during the day but ready to break the mercury at any moment.

Women have been repressing their rage since the dawn of time (to the point of illness–there’s a whole book dedicated to the issue). From birth, we are taught to be “good girls”, to “smile more”, to do whatever it takes to be likeable and palatable. When we’re children, boys can throw their toys and knock down our towers and it’s brushed off because “boys will be boys!” but as girls, we’re reprimanded. We are conditioned to absorb men’s rage as they release it however they please, swallowing down our own because that’s what’s expected of women.

Should a woman ever act in defiance of this expectation, she’s publicly lambasted, her reputation ruined, she’s considered a basket case. Until recently she would have been lobotomised and/or locked up permanently in an insane asylum. And the consequences for those who are non-white, non-able bodied and queer are even worse.

It should come as no surprise then that in the absence of normalising female rage and emotion, women are turning to literature to both release their anger and find validation in it.

For decades, female characters were often confined to narrow archetypes—the caregiver, the romantic interest, the martyr. Today’s unhinged protagonists shatter those expectations, presenting women who are messy, complicated, and unapologetically themselves. They’re not afraid to say what they feel and unleash their rage upon the world. They’re not here to be likeable; they’re here to be real, to paint a real and honest picture of the multitudes we contain and the complexities of the human experience.

I enjoy living vicariously through these “unhinged” characters. Seeing female and queer protagonists act out in ways that are deemed “unacceptable” by polite society is cathartic and thrilling. They say and do the things I fantasise about but would never dare to follow through with in real life.

A cultural shift

The rise of the “Good for Her” genre represents a broader cultural shift as women and the queer community resist the rising attacks on our agency.

In the first 21 days of 2025 already, we’ve seen a frightening rise in anti-trans and misogynistic policies and statements from those in incredible positions of power.

Meta’s move to remove fact-checking will directly impact the queer community as hate speech and misinformation will become a free for all. They’ve also tossed out their DEI initiatives internally and Zuck told Joe Rogan that companies “need more masculine energy”. (whatever tf that means.)

Trump stated in his inauguration speech just this morning that from now on America will recognise only two genders: male and female.

Elon Musk stated that only “high T alpha males” are capable of thinking for themselves; he shared a post on X that said, “This is why a Republic of high status males is best for decision making. Democratic, but a democracy only for those who are free to think.”

I mean, who needs dystopian fiction when you can just read the news at any given moment?

Reading is a political act, and the greater the attempts by the patriarchy to assert dominance and aggression, the more we will fight back and resist, and seek out displays of rebellion that inspire and validate our frustration.

Readers and writers find freedom and solace in sharing stories of oppression and resistance, usually not in the ways in which we’ve been conditioned to believe you should approach these issues. If I’m watching helplessly as the world turns to shit, the only way I can find some semblance of peace is to read about an “unhinged” character who takes matters into their own hands to achieve a sense of justice.

The "Good for Her" genre challenges traditional narratives by celebrating women’s agency, even when it involves breaking societal norms. Its popularity reflects a cultural shift toward embracing female complexity and autonomy, offering both catharsis and critique. The enduring power of the genre lies in its ability to provoke conversations about justice, morality, and empowerment. These stories remind us that, sometimes, rebellion is the most human—and relatable—response to an unjust world.

"Her Body and Other Parties" has been sitting on my shelf for much too long, I NEED to get to it soon

this is interesting! i actually kind of disagree that a lot of these titles explore complex morality—i don’t think amy dunne is both a victim and anti-hero, she’s a compelling character who the text wants you to feel sympathetic for despite all the bad she does but not at any point is she any real kind of victim. i love this genre and i love many, many of these books but soo much of the discussion kind of skates past this idea that they really focus on a singular kind of victimhood that i feel like we can attribute to late-state capitalism and the idea of taking care of one’s self at the cost of community around them. what makes it so interesting is that the morality feels murky when reading because you’re rooting for protagonists because you can relate to their frustrations around patriarchal systems and yet capitalist structures seem to be absent from the conversations. midsummer is always attributed as a Good For Her and the relationship it holds to white hegemonic capitalist and colonist structure / cults ignored because it’s easier to see violence & power as reclamation for the individual in peril rather than looking further at the mass affects re community. anyway very interesting, would love to see you delve into the role capitalism and community plays out in this genre & if you see a correlation between the rise of these stories as relating to the rise of of therapy talk & individualism within late-state capitalism and online spaces.